Introduction to Xamarin Studio

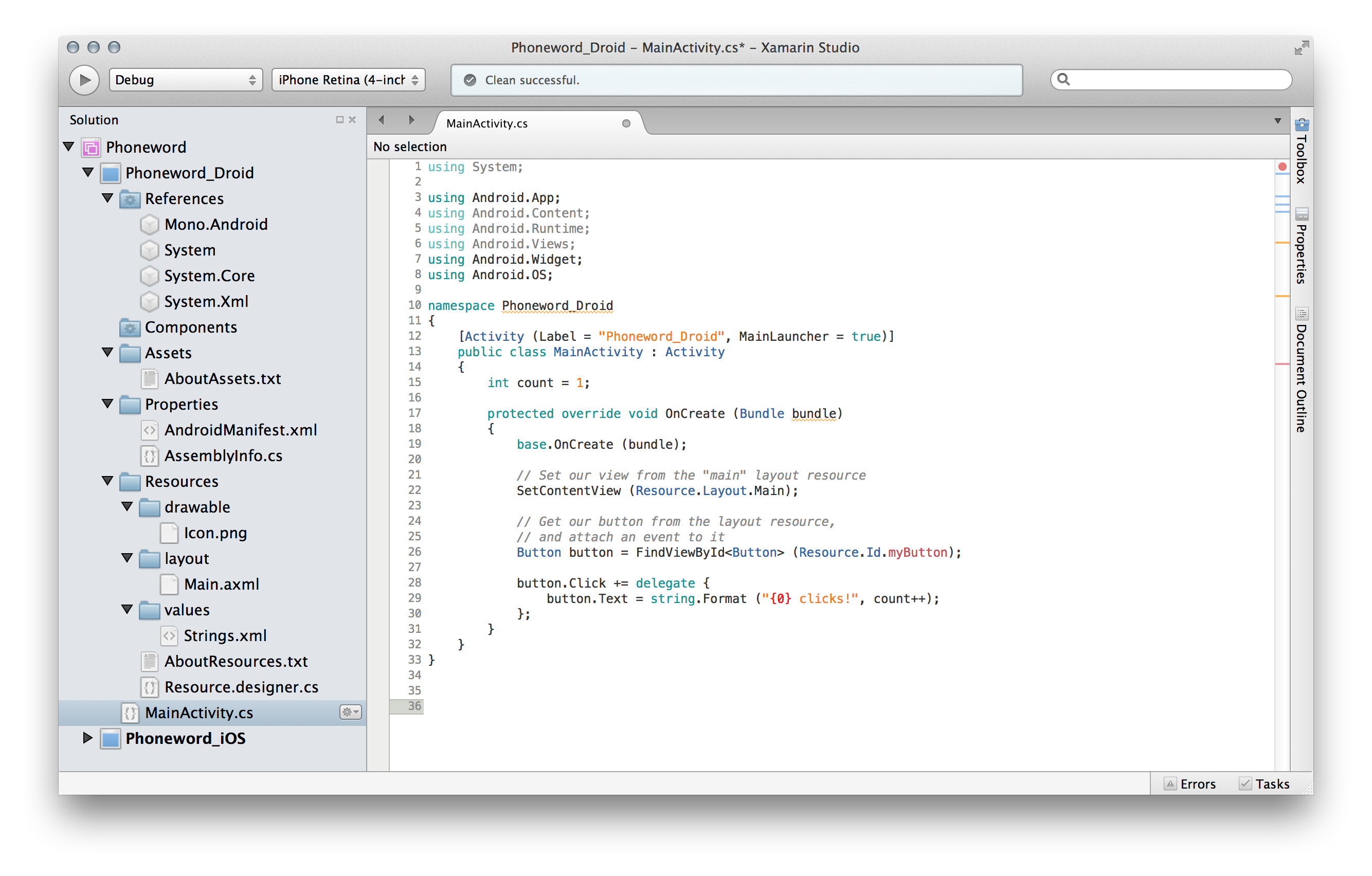

Xamarin Studio is a free, open-source IDE similar to Visual Studio. It features a fully integrated visual designer, a text editor complete with refactoring tools, an assembly browser, source code integration, and more. In this guide we'll learn to use some basic Xamarin Studio features, but if you're new to Xamarin Studio you will want to check out a more in-depth Introduction to Xamarin Studio.

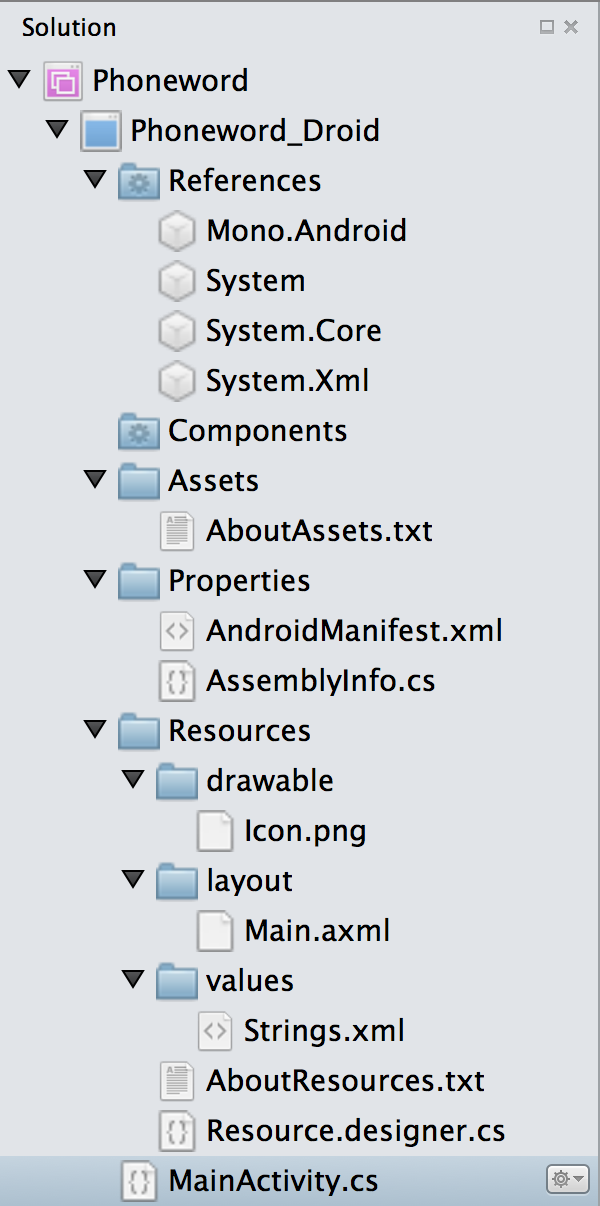

Xamarin Studio follows the Visual Studio practice of organizing code into Solutions and Projects. A Solution is a container that can hold one or more Projects. A Project can be an application (such as iOS or Android), a supporting library, a test application, and more. In our Phoneword app, we added a new Android Project using the Android Application template to the Phoneword Solution we created in the Hello, Android guide. Our Solution looked like this: